- Planet Earth

- Antarctica

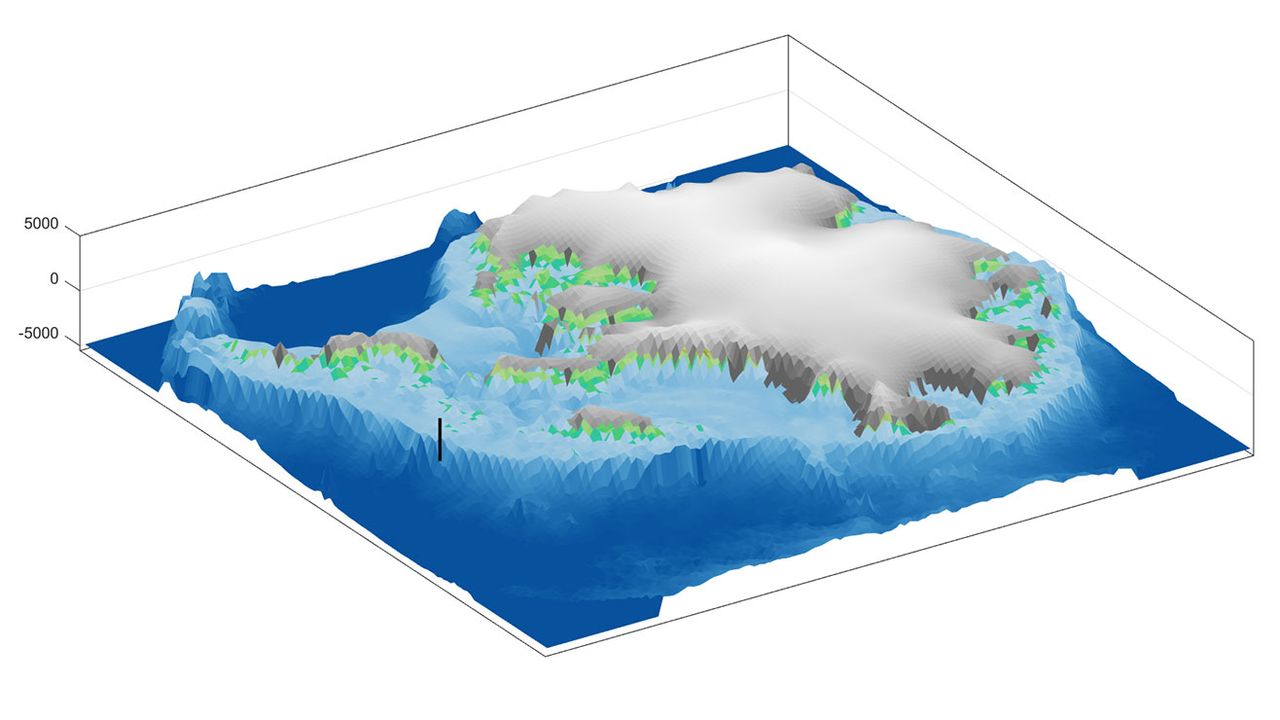

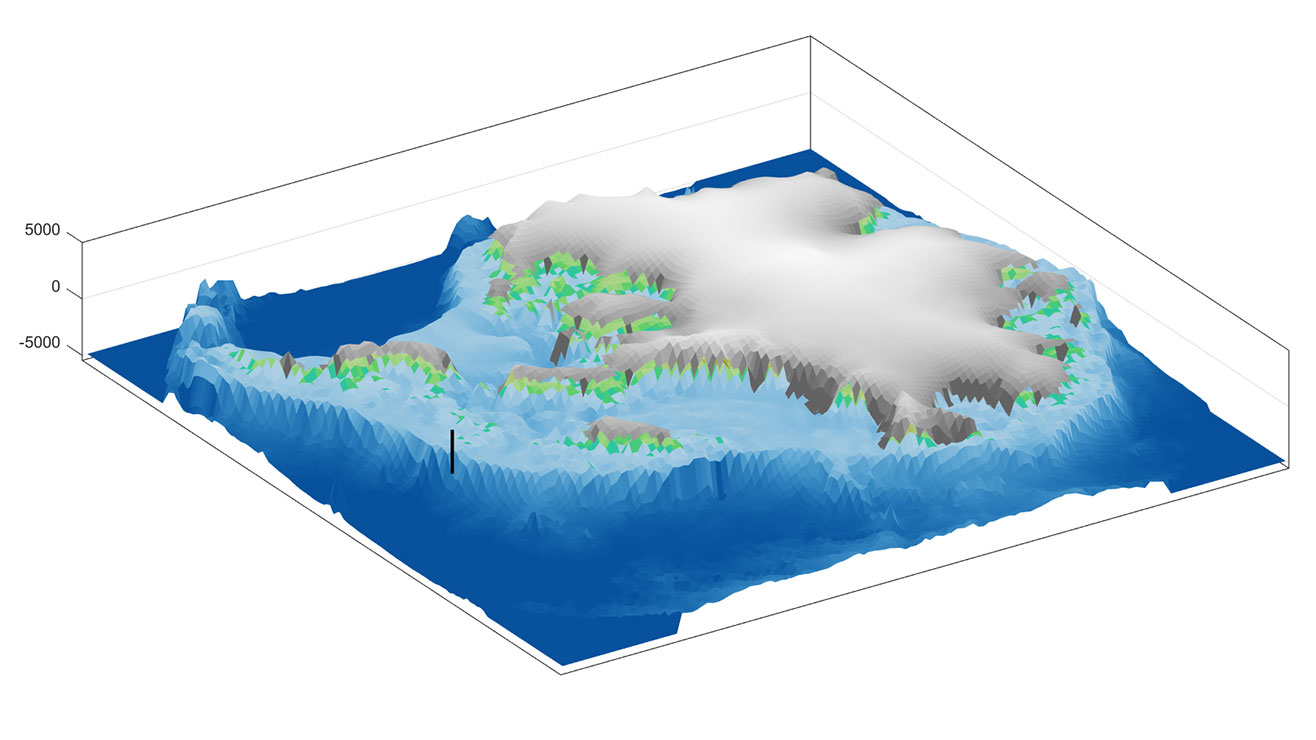

A picture of what West Antarctica looked like when its ice sheet melted in the past can offer insight into the continent’s future as the climate warms.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

The ice that now covers West Antarctica was not there 3.6 million years ago, after a massive collapse of the ice sheet during a warming period.

(Image credit: Anna Ruth Halberstadt / CC BY-NC-ND)

Share

Share by:

The ice that now covers West Antarctica was not there 3.6 million years ago, after a massive collapse of the ice sheet during a warming period.

(Image credit: Anna Ruth Halberstadt / CC BY-NC-ND)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

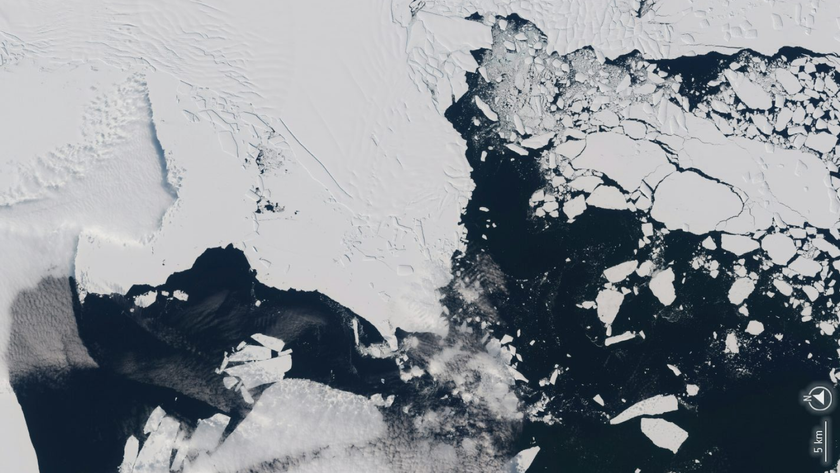

Due to its thick, vast ice sheet, Antarctica appears to be a single, continuous landmass centered over the South Pole and spanning both hemispheres of the globe. The Western Hemisphere sector of the ice sheet is shaped like a hitchhiker’s thumb – an apt metaphor, because the West Antarctic ice sheet is on the go. Affected by Earth’s warming oceans and atmosphere, the ice sheet that sits atop West Antarctica is melting, flowing outward and diminishing in size, all at an astonishing pace.

Much of the discussion about the melting of massive ice sheets during a time of climate change addresses its effects on people. That makes sense: Millions will see their homes damaged or destroyed by rising sea levels and storm surges.

You may like-

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

-

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

-

Methane leaks multiplying beneath Antarctic ocean spark fears of climate doom loop

Methane leaks multiplying beneath Antarctic ocean spark fears of climate doom loop

In layers of sediment accumulated on the sea floor over millions of years, researchers like us are finding evidence that when West Antarctica melted, there was a rapid uptick in onshore geological activity in the area. The evidence foretells what’s in store for the future.

A voyage of discovery

As far back as 30 million years ago, an ice sheet covered much of what we now call Antarctica. But during the Pliocene Epoch, which lasted from 5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago, the ice sheet on West Antarctica drastically retreated. Rather than a continuous ice sheet, all that remained were high ice caps and glaciers on or near mountaintops.

About 5 million years ago, conditions around Antarctica began to warm, and West Antarctic ice diminished. About 3 million years ago, all of Earth entered a warm climate phase, similar to what is happening today.

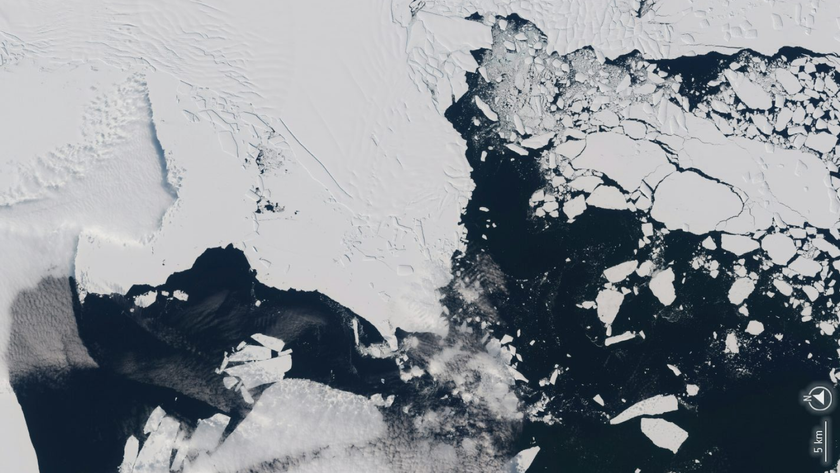

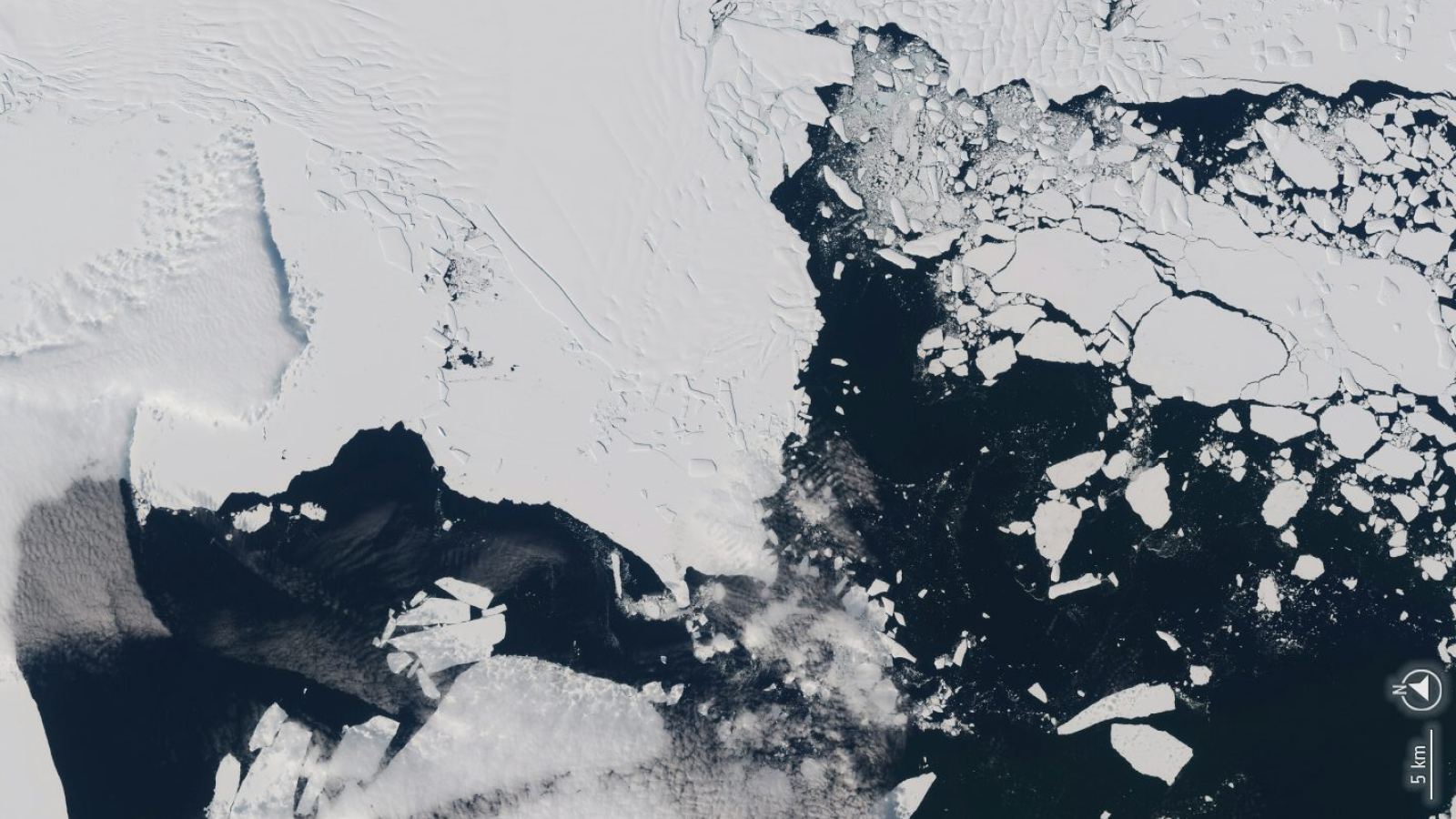

Glaciers are not stationary. These large masses of ice form on land and flow toward the sea, moving over bedrock and scraping off material from the landscape they cover, and carrying that debris along as the ice moves, almost like a conveyor belt. This process speeds up when the climate warms, as does calving into the sea, which forms icebergs. Debris-laden icebergs can then carry that continental rock material out to sea, dropping it to the sea floor as the icebergs melt.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

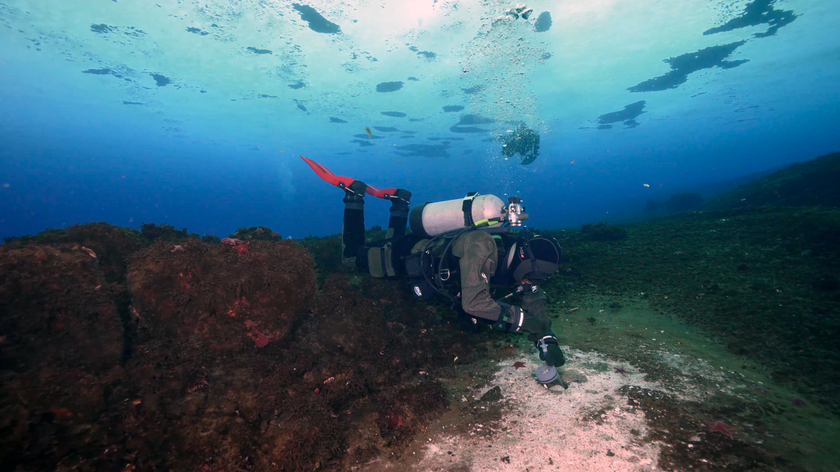

In early 2019, we joined a major scientific trip – International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 379 – to the Amundsen Sea, south of the Pacific Ocean. Our expedition aimed to recover material from the seabed to learn what had happened in West Antarctica during its melting period all that time ago.

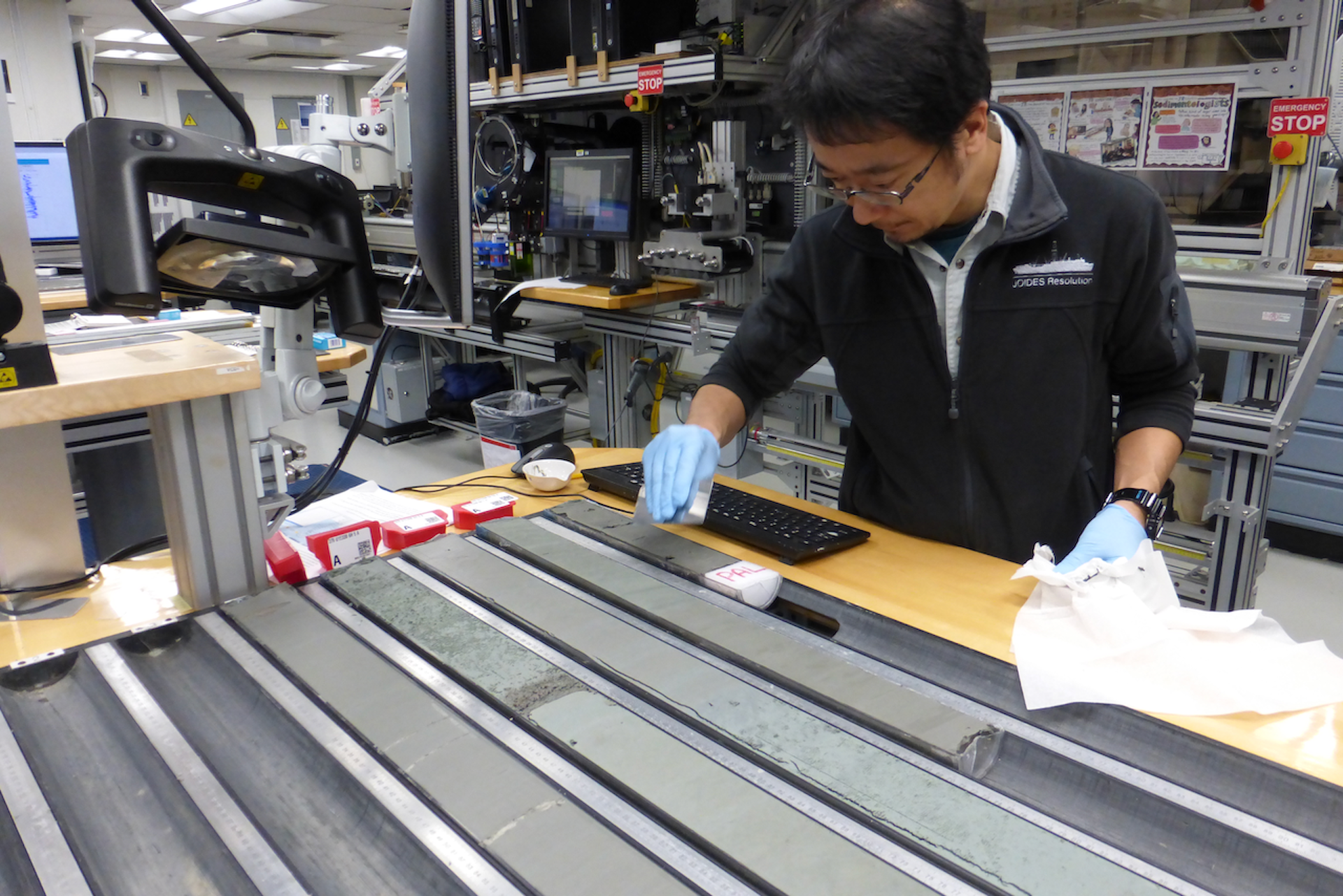

Aboard the drillship JOIDES Resolution, workers lowered a drill nearly 13,000 feet (3,962 meters) to the sea floor and then drilled 2,605 feet (794 meters) into the ocean floor, directly offshore from the most vulnerable part of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

The drill brought up long tubes called “cores,” containing layers of sediments deposited between 6 million years ago and the present. Our research focused on sections of sediment from the time of the Pliocene Epoch, when Antarctica was not entirely ice-covered.

You may like-

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

-

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

-

Greenland is twisting, tensing and shrinking due to the 'ghosts' of melted ice sheets

Greenland is twisting, tensing and shrinking due to the 'ghosts' of melted ice sheets

An unexpected finding

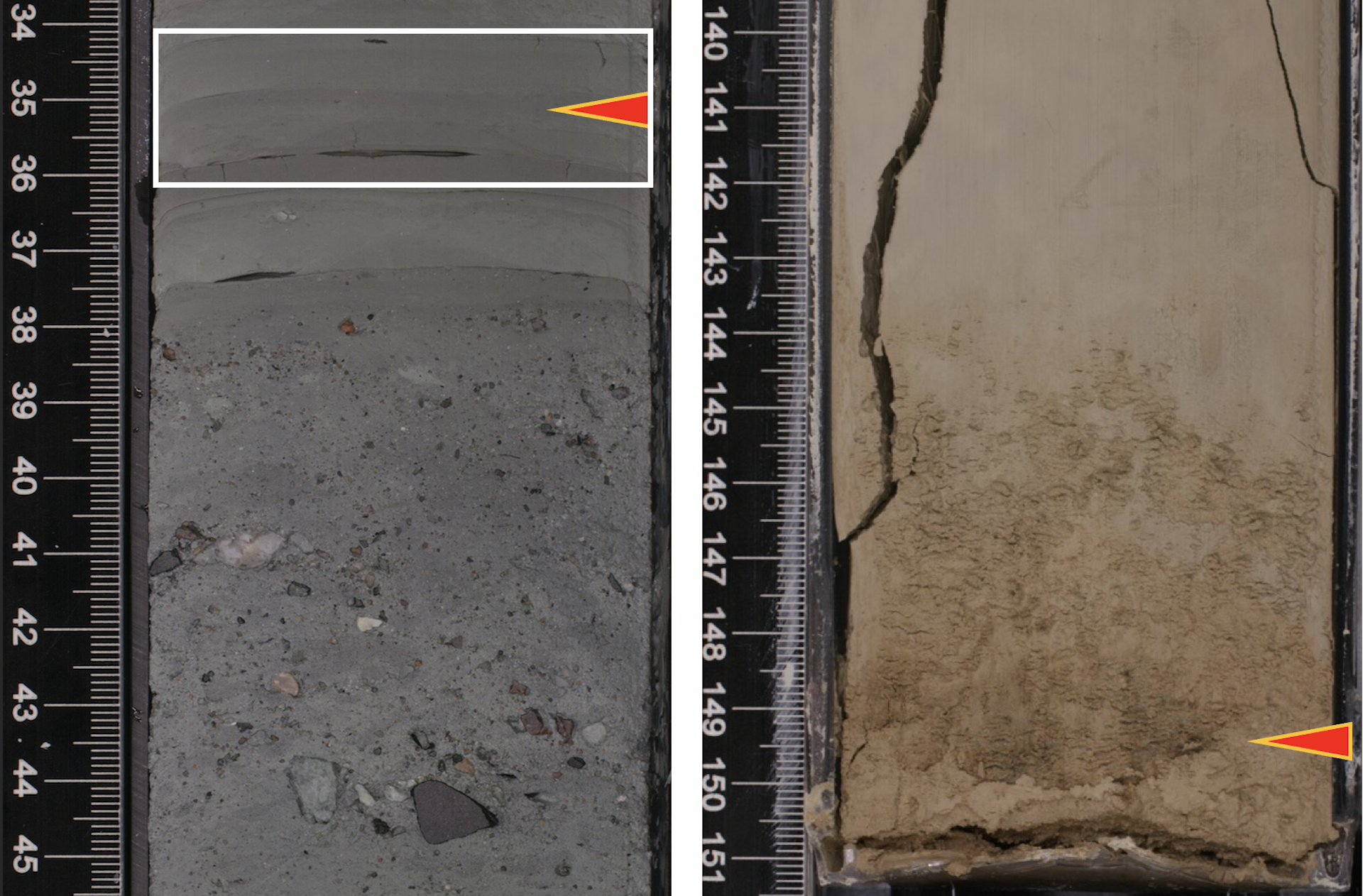

While onboard, one of us, Christine Siddoway, was surprised to discover an uncommon sandstone pebble in a disturbed section of the core. Sandstone fragments were rare in the core, so the pebble’s origin was of high interest. Tests showed that the pebble had come from mountains deep in the Antarctic interior, roughly 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) from the drill site.

For this to have happened, icebergs must have calved from glaciers flowing off interior mountains and then floated toward the Pacific Ocean. The pebble provided evidence that a deep-water ocean passage – rather than today’s thick ice sheet – existed across the interior of what is now Antarctica.

After the expedition, once the researchers returned to their home laboratories, this finding was confirmed by analyzing silt, mud, rock fragments, and microfossils that also came up in the sediment cores. The chemical and magnetic properties of the core material revealed a detailed timeline of the ice sheet’s retreats and advances over many years.

One key sign came from analyses led by Keiji Horikawa. He tried to match thin mud layers in the core with bedrock from the continent, to test the idea that icebergs had carried such materials very long distances. Each mud layer was deposited right after a deglaciation episode, when the ice sheet retreated, that created a bed of iceberg-carried pebbly clay. By measuring the amounts of various elements, including strontium, neodymium and lead, he was able to link specific thin layers of mud in the drill cores to chemical signatures in outcrops in the Ellsworth Mountains, 870 miles (1400 km) away.

Horikawa discovered not just one instance of this material but as many as five mud layers deposited between 4.7 million and 3.3 million years ago. That suggests the ice sheet melted and open ocean formed, then the ice sheet regrew, filling the interior, repeatedly, over short spans of thousands to tens of thousands of years.

AIS Pliocene heartbeat - YouTube Watch On

Watch On

Creating a fuller picture

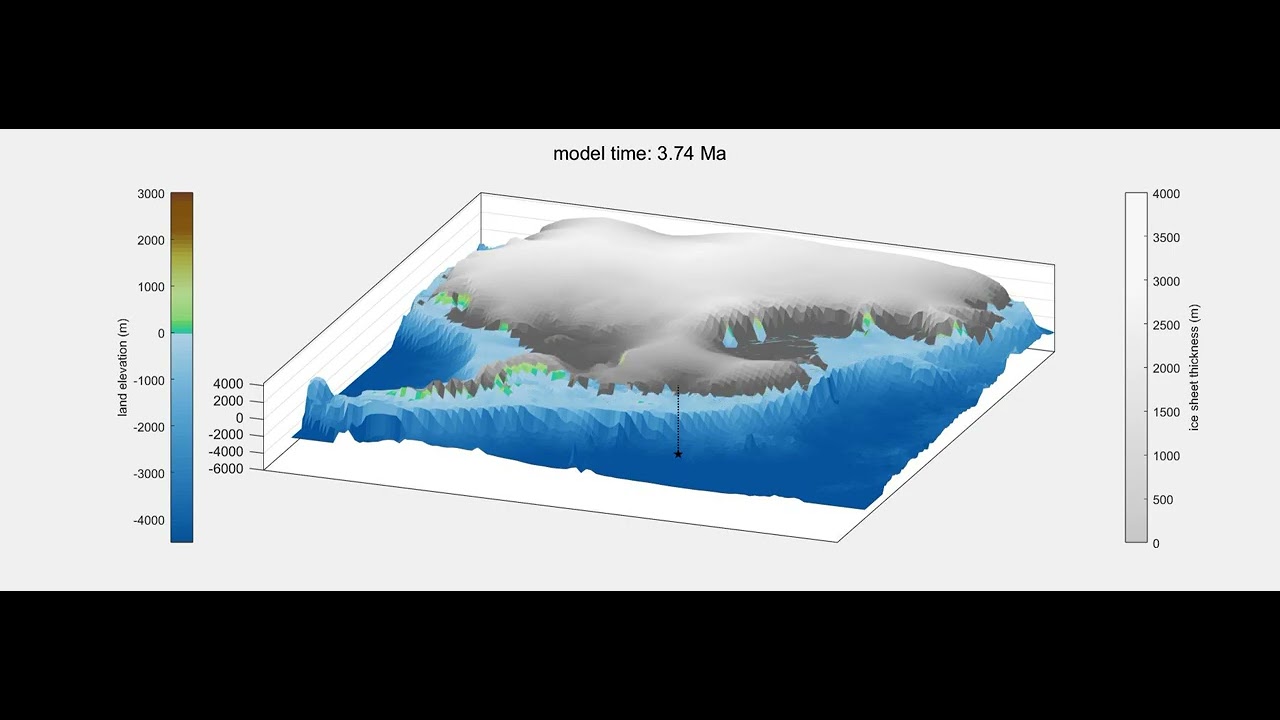

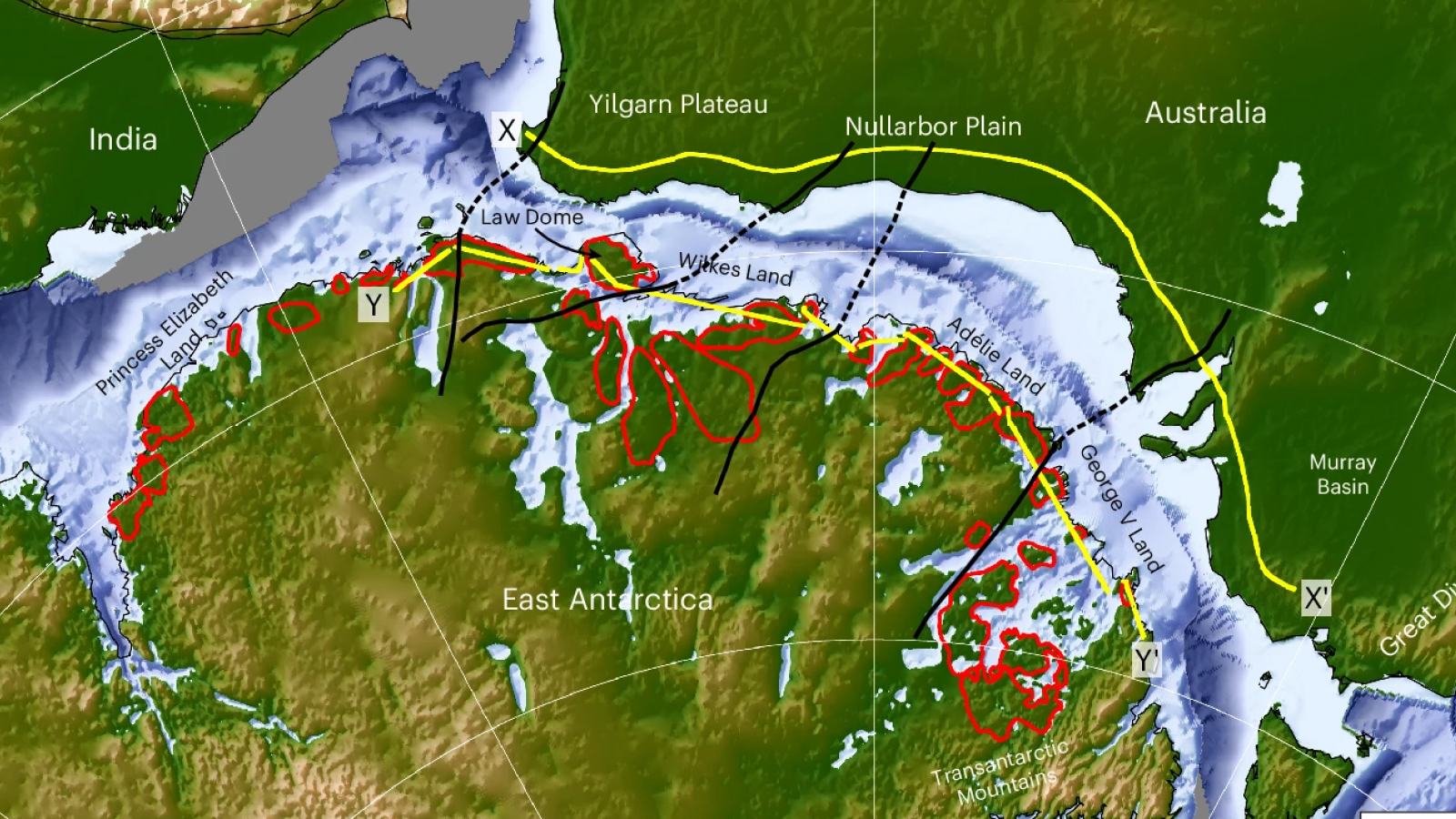

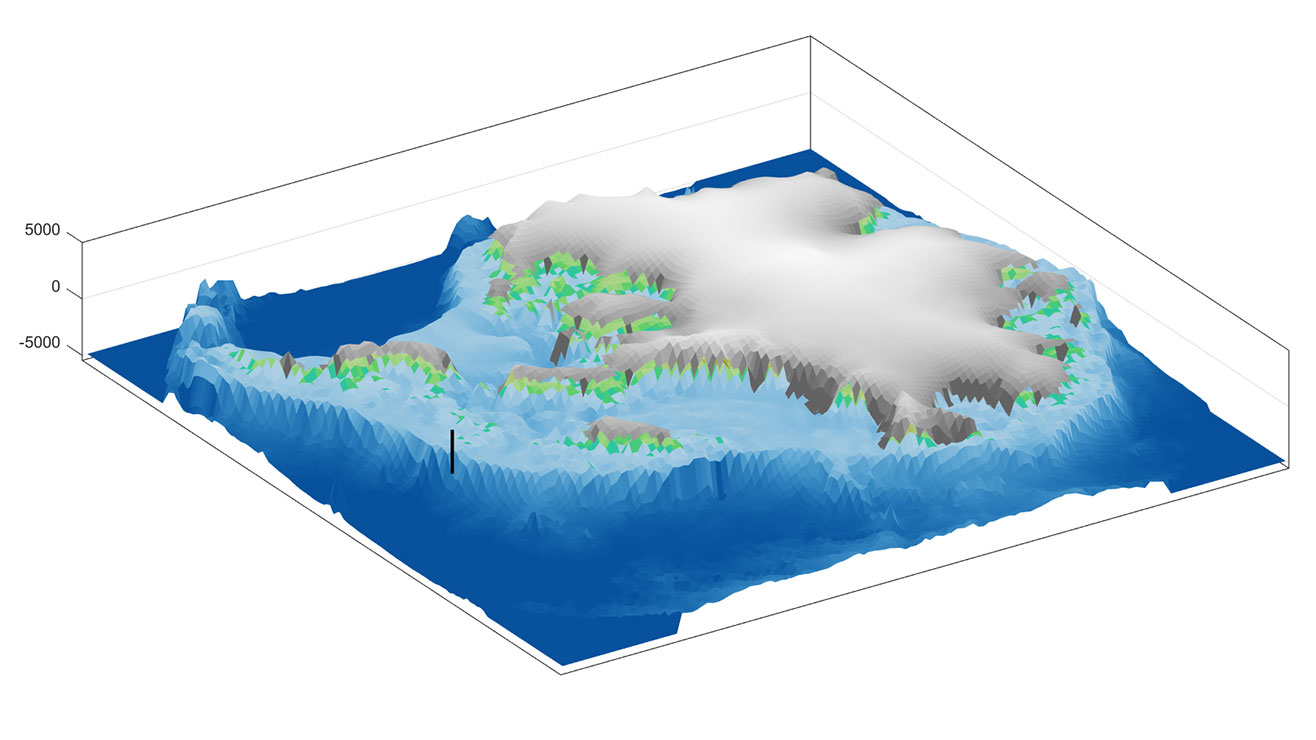

Teammate Ruthie Halberstadt combined this chemical evidence and timing in computer models showing how an archipelago of ice-capped, rugged islands emerged as ocean replaced the thick ice sheets that now fill Antarctica’s interior basins.

The biggest changes happened along the coast. The model simulations show a rapid increase in iceberg production and a dramatic retreat of the edge of the ice sheet toward the Ellsworth Mountains. The Amundsen Sea became choked with icebergs produced from all directions. Rocks and pebbles embedded in the glaciers floated out to sea within the icebergs and dropped to the seabed as the icebergs melted.

Long-standing geological evidence from Antarctica and elsewhere around the world shows that as ice melts and flows off the land, the land itself rises because the ice no longer presses it down. That shift can cause earthquakes, especially in West Antarctica, which sits above particularly hot areas of the Earth’s mantle that can rebound at high rates when the ice above them melts.

The release of pressure on the land also increases volcanic activity – as is happening in Iceland in the present day. Evidence of this in Antarctica comes from a volcanic ash layer that Siddoway and Horikawa identified in the cores, formed 3 million years ago.

The long-ago loss of ice and upward motions in West Antarctica also triggered massive rock avalanches and landslides in fractured, damaged rock, forming glacial valley walls and coastal cliffs. Collapses beneath the sea displaced vast amounts of sediment from the marine shelf. No longer held in place by the weight of glacier ice and ocean water, huge masses of rock broke away and surged into the water, producing tsunamis that unleashed more coastal destruction.

The rapid onset of all these changes made deglaciated West Antarctica a showpiece for what has been called “catastrophic geology.”

The rapid upswell of activity resembles what has happened elsewhere on the planet in the past. For instance, at the end of the last Northern Hemisphere ice age, 15,000 to 18,000 years ago, the region between Utah and British Columbia was subjected to floods from bursting glacial meltwater lakes, land rebound, rock avalanches and increased volcanic activity. In coastal Canada and Alaska, such events continue to occur today.

As glaciers melt, scientists study potential for more violent volcanic eruptions - YouTube Watch On

Watch On

Dynamic ice sheet retreat

Our team’s analysis of rocks’ chemical makeup makes clear that West Antarctica doesn’t necessarily undergo one gradual, massive shift from ice-covered to ice-free, but rather swings back and forth between vastly different states. Each time the ice sheet disappeared in the past, it led to geological mayhem.

Related stories—6 million-year-old ice discovered in Antarctica shatters records — and there's ancient air trapped inside

—Methane leaks multiplying beneath Antarctic ocean spark fears of climate doom loop

—Scientists discover 85 'active' lakes buried beneath Antarctica's ice

The future implication for West Antarctica is that when its ice sheet next collapses, the catastrophic events will return. This will happen repeatedly, as the ice sheet retreats and advances, opening and closing the connections between different areas of the world’s oceans.

This dynamic future may bring about equally swift responses in the biosphere, such as algal blooms around icebergs in the ocean, leading to an influx of marine species into newly opened seaways. Vast tracts of land upon West Antarctic islands would then open up to growth of mossy ground cover and coastal vegetation that would turn Antarctica more green than its current icy white.

Our data about the Amundsen Sea’s past and the resulting forecast indicate that onshore changes in West Antarctica will not be slow, gradual or imperceptible from a human perspective. Rather, what happened in the past is likely to recur: geologically rapid shifts that are felt locally as apocalyptic events such as earthquakes, eruptions, landslides and tsunamis – with worldwide effects.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Christine SiddowayProfessor of Geology, Colorado College

Christine SiddowayProfessor of Geology, Colorado CollegeChristine Siddoway is a professor of geology at Colorado College. Dr. Siddoway's research interests include structural and metamorphic geology; tectonic development of West Antarctica and New Zealand within Gondwana; Rocky Mountains tectonics; the role of melt in deformation of migmatites; and sandstone injectites.

With contributions from Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Greenland is twisting, tensing and shrinking due to the 'ghosts' of melted ice sheets

Greenland is twisting, tensing and shrinking due to the 'ghosts' of melted ice sheets

Antarctica's Southern Ocean might be gearing up for a thermal 'burp' that could last a century

Antarctica's Southern Ocean might be gearing up for a thermal 'burp' that could last a century

Hidden, supercharged 'thermostat' may cause Earth to overcorrect for climate change

Hidden, supercharged 'thermostat' may cause Earth to overcorrect for climate change

Arctic Ocean methane 'switch' that helped drive rapid global warming discovered

Latest in Antarctica

Arctic Ocean methane 'switch' that helped drive rapid global warming discovered

Latest in Antarctica

6 million-year-old ice discovered in Antarctica shatters records — and there's ancient air trapped inside

6 million-year-old ice discovered in Antarctica shatters records — and there's ancient air trapped inside

Methane leaks multiplying beneath Antarctic ocean spark fears of climate doom loop

Methane leaks multiplying beneath Antarctic ocean spark fears of climate doom loop

Scientists discover 85 'active' lakes buried beneath Antarctica's ice

Scientists discover 85 'active' lakes buried beneath Antarctica's ice

40-year-old 'queen of icebergs' A23a is no longer world's biggest after losing several 'very large chunks' since May

40-year-old 'queen of icebergs' A23a is no longer world's biggest after losing several 'very large chunks' since May

Abrupt changes taking place in Antarctica 'will affect the world for generations to come'

Abrupt changes taking place in Antarctica 'will affect the world for generations to come'

Scientists discover long-lost giant rivers that flowed across Antarctica up to 80 million years ago

Latest in Opinion

Scientists discover long-lost giant rivers that flowed across Antarctica up to 80 million years ago

Latest in Opinion

Should humans colonize other planets?

Should humans colonize other planets?

'Gospel stories themselves tell of dislocation and danger': A historian describes the world Jesus was born into

'Gospel stories themselves tell of dislocation and danger': A historian describes the world Jesus was born into

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

Do you think you can tell an AI-generated face from a real one?

Do you think you can tell an AI-generated face from a real one?

'Artificial intelligence' myths have existed for centuries – from the ancient Greeks to a pope's chatbot

'Artificial intelligence' myths have existed for centuries – from the ancient Greeks to a pope's chatbot

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

LATEST ARTICLES

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

LATEST ARTICLES 1James Webb telescope confirms a supermassive black hole running away from its host galaxy at 2 million mph, researchers say

1James Webb telescope confirms a supermassive black hole running away from its host galaxy at 2 million mph, researchers say- 2Orbiting satellites could start crashing into one another in less than 3 days, theoretical new 'CRASH Clock' reveals

- 3Vera C. Rubin Observatory discovers enormous, record-breaking asteroid in first 7 nights of observations

- 4New US food pyramid recommends very high protein diet, beef tallow as healthy fat option, and full-fat dairy

- 5Rare 2,000-year-old war trumpet, possibly linked to Celtic queen Boudica, discovered in England