Art institutions in the United States continue to force elections and exclude workers from eligibility to join unions, running counter to their own purported values and goals.

Amanda Tobin Ripley

January 7, 2026

— 6 min read

Amanda Tobin Ripley

January 7, 2026

— 6 min read

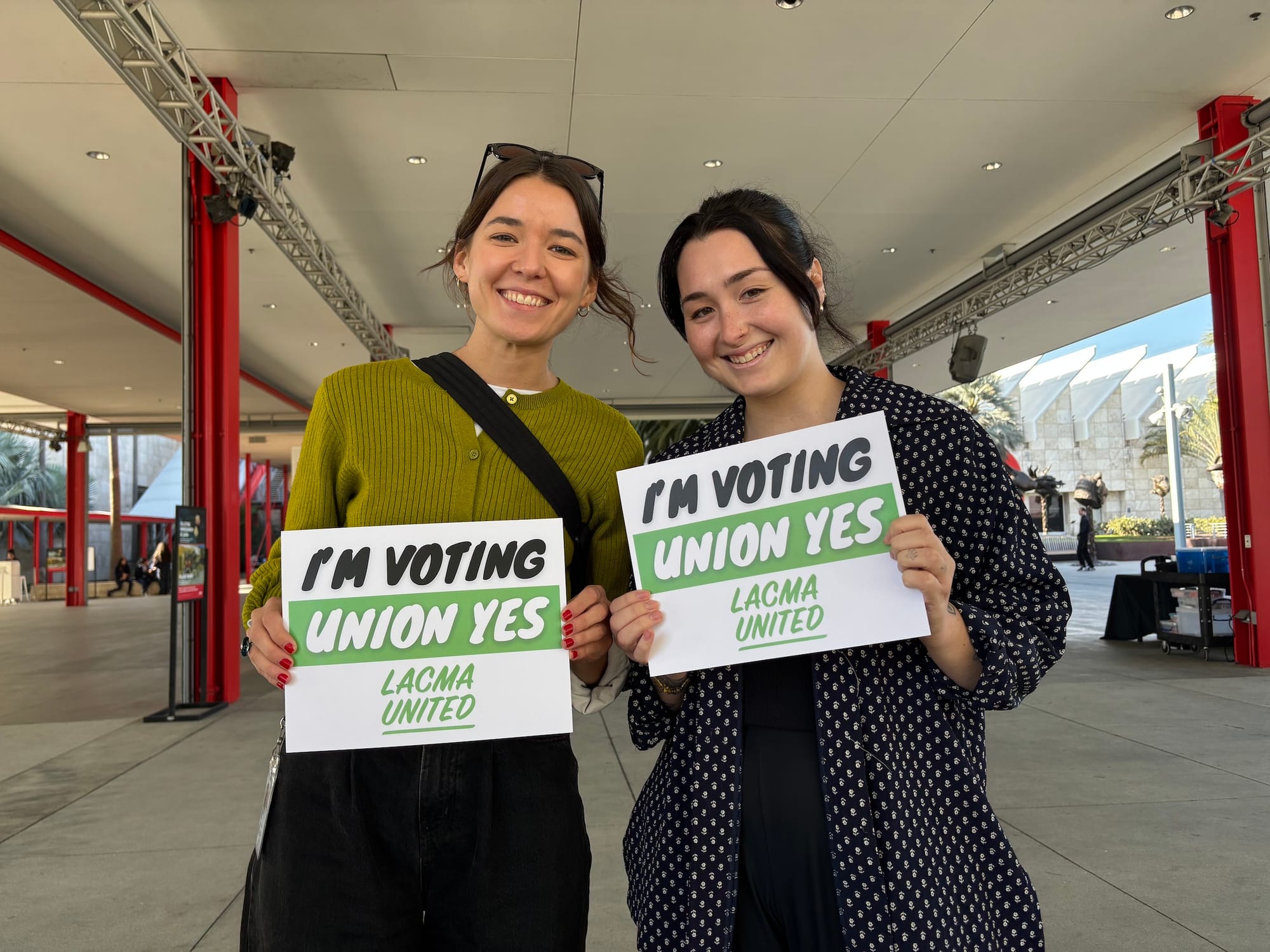

LACMA workers celebrate after winning their union election in December 2025. (all images courtesy LACMA United)

LACMA workers celebrate after winning their union election in December 2025. (all images courtesy LACMA United)

The unionization wave across museums in the United States just scored major wins. Workers at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), who announced their intent to unionize on October 29, won their union election on December 16 with 96% of the vote, while workers at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced their campaigns on November 4 and November 17, respectively. These workplaces are behemoths among museums, and unions have the power to materially change the realities of the thousands of people working at these institutions and to profoundly shift labor-management relations in the sector.

In a testimony to the power of their organizing work, 100% of union elections at private, nonprofit art museums in the US have been successful since the contemporary unionization wave began in 2019. You might think, then, that museum leadership would recognize the futility of forcing a union election in hopes that workers will vote “no.” Only 21% of campaigns to date, however, have received voluntary recognition; museum leadership has instead insisted on holding elections. Why would management do this, especially given that it guarantees negative press, damages employer-employee relations for years to come, and highlights the disparity between their actions and their mission statements?

Simply put, forcing an election helps leadership keep its unilateral control over a museum. An election allows administrators to try to both dissuade workers from voting for the union and challenge individual workers’ eligibility to be in it, all with the aim of shrinking its size and, therefore, its power.

Challenging worker eligibility has been a favorite response of museum leaders to this current wave of unionization, as I’ve discovered in my own experience organizing and researching museum unions, including for the organization Museums Moving Forward’s Art Museum Unions Index. There is a clear pattern of museum leadership weaponizing the time between campaign announcement and election to challenge the union’s power.

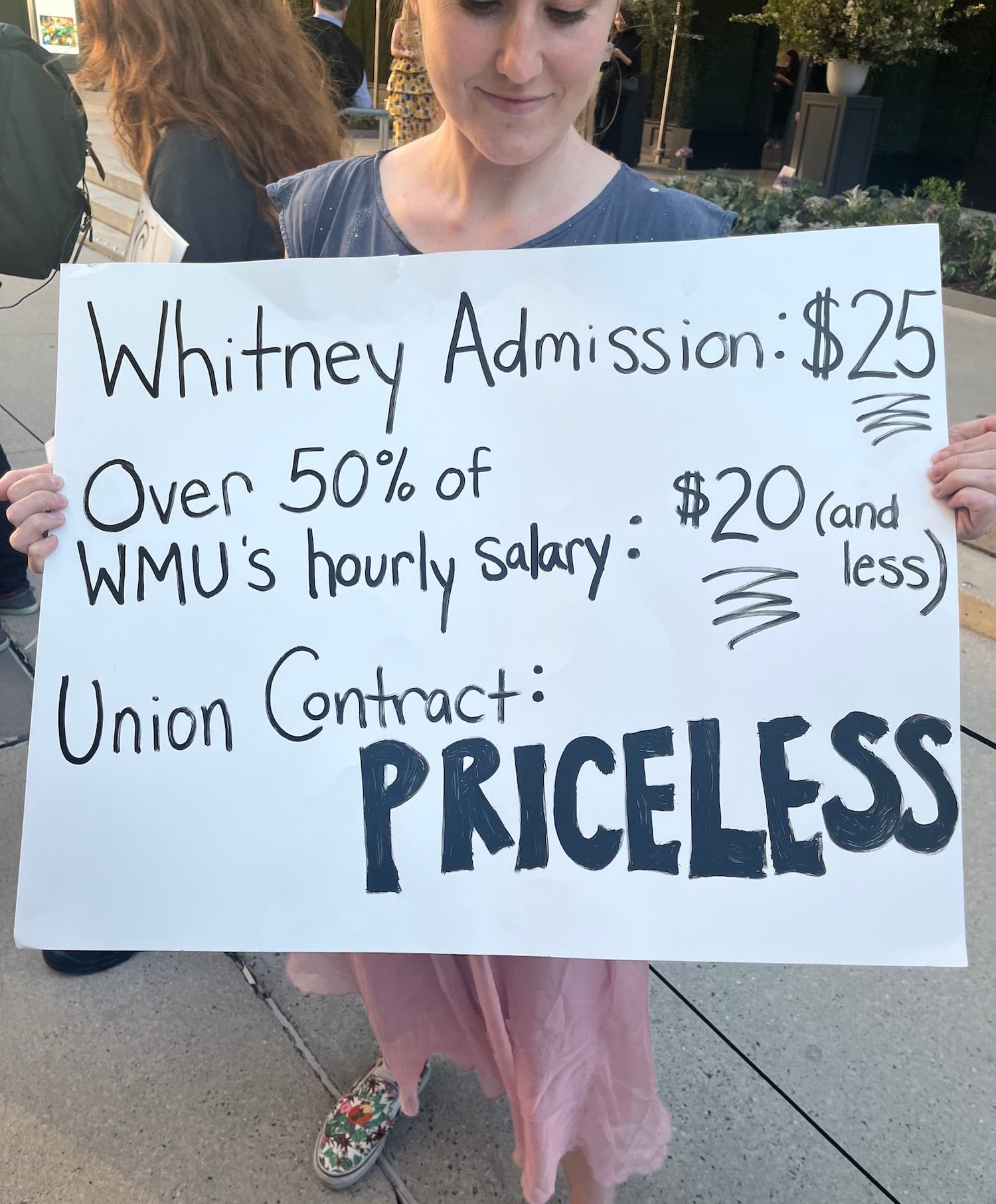

A worker holds a sign outside the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan on May 17, 2022, during a protest for fair wages during a gala. The union reached an agreement with the museum in March of 2023. (photo Jasmine Liu/Hyperallergic)

A worker holds a sign outside the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan on May 17, 2022, during a protest for fair wages during a gala. The union reached an agreement with the museum in March of 2023. (photo Jasmine Liu/Hyperallergic)To be legally recognized as a union, workers secure governmental certification through one of two means: The employer can either choose to recognize the union as-is or require the union to hold an election and win a majority vote. Furthermore, under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), signed into law in 1935, certain employees are ineligible for membership in the same union: managers, security guards, and confidential employees (like Human Resources workers who handle sensitive information). Excluding managers — defined as those with hiring and firing power — is an attempt to prevent a conflict of interest among workers and their supervisors. Whose side would a union take during a disciplinary dispute if both the discipliner and the disciplined were in the same union?

But “manager” is a complicated and ambiguous term in the museum world. Most workers with “manager” in their title supervise programs, not people. Time and time again, however, museum leaders have argued that managers of teen programs, visitor services, or curatorial affairs are ineligible for union membership, leading to prolonged (and expensive) disputes that often require formal testimonials and third-party arbitrations.

The second tool museum leadership uses to weaken union bargaining power is to lean on the NLRA’s so-called “guard exclusion” provision or Section 9(3)(b). It seemingly mandates a clear dividing line between security guards and all other staff members. The provision was added to the NLRA under the 1947 Taft-Hartley amendments — which, notably, then-President Harry Truman vetoed as unions decried it as a “slave-labor bill,” only to be overruled by a Senate beholden to corporate, anti-Communist, and White Southern Democrats’ interests. Originally designed to exclude “plant guards” and “watchmen,” Section 9(3)(b) aims to prevent a conflict of interest in the case of a strike or other direct action, which could cause harm to the company’s property; the guards needed to be on hand to protect the factory from their unionized coworkers.

This provision has led to widespread confusion regarding museum security guards, whose daily functions include, yes, protecting the artwork and property, but also supporting visitor experience through wayfinding and answering questions about exhibitions and institutional history, among other responsibilities.

When unions are voluntarily recognized, however, leadership agrees to work with the union as defined by its members, which can include security guards. It is, in fact, the only legal way for security guards to be in the same union as other staff members. To date, however, only the Baltimore Museum of Art Union, Walker Worker Union, Walters Workers United, and Tacoma Art Museum Workers United have successfully established wall-to-wall units that include guards, using voluntary recognition.

Given the racial demographics of museum staff — the greatest percentage of people of color work in building operations, which include security departments — the guard exclusion provision contributes to a specific and pervasive type of siloing along racial lines. When excluded from a wall-to-wall union of workers from all other departments at the museum, Section 9(3)(b) forces security guards to make one of three choices. They can organize with a police union (as the guards at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine had to do after they were excluded from the UAW Local 2110 union), form an independent union and forego the legal and financial support of parent union affiliation (as guards at the Seattle Museum of Art and the Frye Art Museum chose to do), or remain unprotected individual employees without a union.

Kristin Nyquist, Tessitura manager, and Allyson Armstrong, annual giving coordinator, at LACMA

Kristin Nyquist, Tessitura manager, and Allyson Armstrong, annual giving coordinator, at LACMAThe recent Data Study from Museums Moving Forward demonstrates how precarious this unprotected status can be. The organization found that more than a quarter of museum workers do not make a living wage; experiences of precarity, harassment, and in-work poverty are unevenly distributed, affecting people of color and nonbinary employees at higher rates than White and cis workers; and that non-unionized workers earn only 85% of what their unionized counterparts earn on a weekly basis. Labor unions have, on the whole, helped to shrink the racial wealth gap in the US and contributed to more robust and equitable democracies. But their potential to do so in the art museum sector remains limited by these job classification divides, reinforced through union election procedures.

On November 6, LACMA United reported that their request for voluntary recognition was denied, and that museum management was insisting on a union election. Despite a public pressure campaign to ask management to reconsider, their election was held on December 15 and 16 — they won by a landslide. Meanwhile, though The Met Union did not publicly ask for voluntary recognition, the museum has retained Littler Mendelson, the “union avoidance” consultancy firm engaged by Starbucks and Amazon, according to the case page from the National Labor Relations Board. The union’s election is scheduled for next week on January 13 and 15. DIA Workers United, meanwhile, is still waiting for a response to its November 4 request for voluntary recognition.

Insisting on union elections runs counter to museums’ stated values. The choice to do so maintains structural exclusions and exposes the hypocrisies of art museums, spaces we trust with preserving and ensuring access to our shared cultural heritage. In this current era of political assaults on DEI, federal attempts to control and suppress the narratives told in museum exhibitions, and relentless racist attacks by ICE, museum leadership should abolish the practice of insisting on union certification by election only. Voluntary recognition not only establishes a labor-management relationship based on a faith in future cooperation and trust, but also allows for stronger unions made up of more diverse workers. Leadership at LACMA and The Met squandered these opportunities to actually lead, and to forge new standards of museum operations via voluntary recognition. To management at DIA and countless other museums whose employees may be in the process of unionizing: It’s time to stop excluding workers, boldly resist further capitulation to the Trump regime, and recognize your unions.